From a serious policymaking point of view, the question as to whether “Ghana should go to the IMF” is not a complete, or particularly meaningful, one.

The IMF has many product lines, designed for different purposes, so the more appropriate questions are:

- Should Ghana go for a/some IMF product(s)/program(s)?

- If yes, which?

- What are the costs and benefits?

In actual fact, two of the key functions of the IMF result in some pretty automatic programs for all 190 countries in the world that have signed the Bretton Woods Agreement.

It helps to recall that as the second world war was drawing to a close, and the increasingly triumphant American-led bloc was designing how they were going to govern the world they were about to inherit, economic “viruses” like hyperinflation and shortage of goods, both in the earlier interwar period and during the war, had already shown clearly how contagious they could be if countries do not work to stem their spread. Just like COVID-19.

Even a casual look at the four main functions of the IMF immediately points out which two should be considered “baseline” for all participating countries:

- Surveillance of the international monetary system

- Monitoring of members’ economic and financial policies

- Provision of Fund resources to member countries in need

- Delivery of technical assistance and financial services.

All countries in good standing and in “continuing communion” with the IMF cooperate with it on the first two functions. That fact can be translated to mean that every one of the 190 countries have a program of some sort with the IMF. The famous Article IV “Consultations” that see the IMF hold bilateral discussions with member state governments almost every year is legally grounded in the surveillance and monitoring powers granted to the Fund under the 1944 Agreement.

So, presumably, when sensitivities emerge about whether Ghana should do business with the IMF, the issue is about the last two functions: borrowing money and/or being subjected to something akin to “technical supervision” of how the government of Ghana conducts its business of governing the economy. But even in respect of these two areas, as I have already stated above, the Fund is like a restaurant with a menu. There are varied dishes and a bit of room for some customization. Every program is designed on the back of a bespoke agreement. Much depends on a country’s negotiating skill.

It is a bit sad, for all the foregoing reasons, for the Finance Ministry to simply bundle everything IMF into the “bailout” category. By making the government’s IMF posture look like a patriotic avoidance of beggary and prostration before a foreign overlord, the Finance Ministry has completely distorted a proper discussion about “what Ghana can use the IMF for” strategically.

Such conduct follows in a line of worrying missteps in the ongoing management of Ghana’s revenue crisis. Sound analysis requires robust debate about all the options available to Ghana in these trying times. The “echo chamber” style of governance, often neglecting facts and data, is estranging the policy community in Accra, who no longer finds a counterpart in the government for genuinely robust policy engagement.

IMANI’s Professor Bopkin is something of a scholar of Ghana-IMF relations. He has helpfully produced the chart and table below to show that Ghana is the 5th most enthusiastic IMF customer in Africa. The country has approached the Fund 16 times since it joined in 1957. Since then, usually after every political transition or onset of major reforms, Ghana “goes” to the IMF.

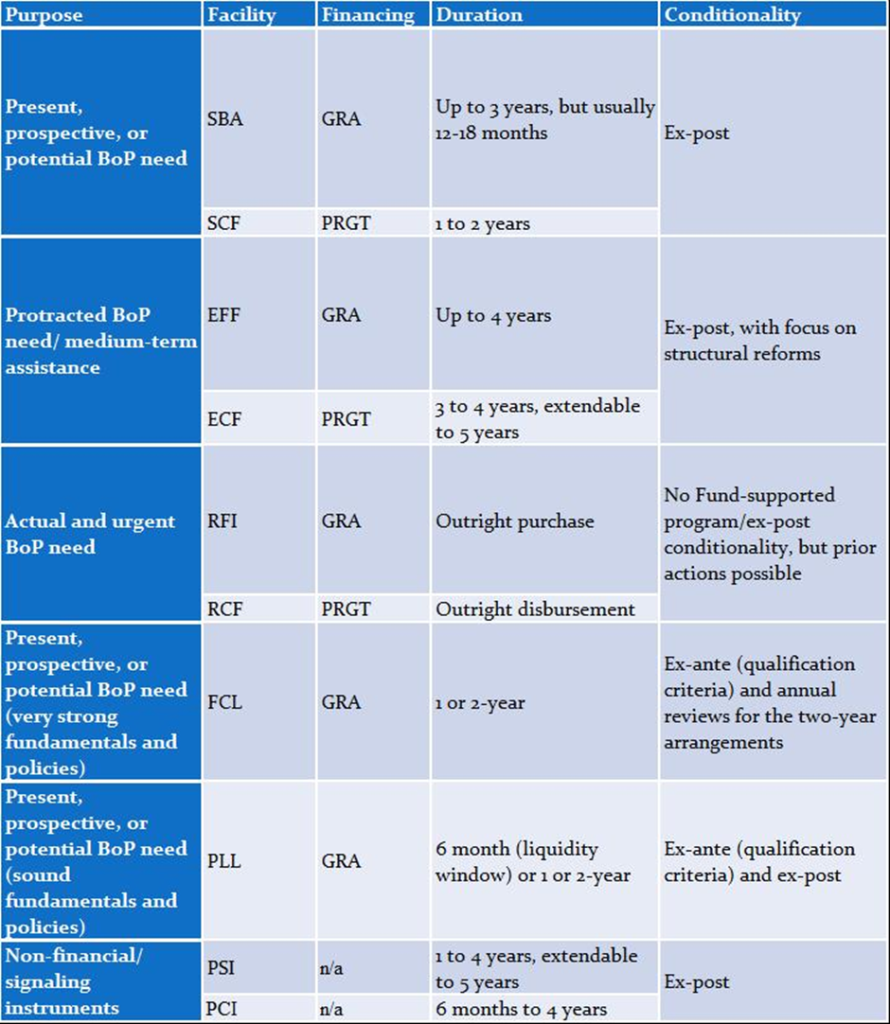

A deeper dive into the details shows that the aversion of some economic managers for IMF “conditionality” (terms or conditions associated with some of the IMF products) generally result from the type of products Ghana usually qualifies for. Ghana’s IMF engagements have often been characterised by long-term (3 to 5 years) and intrusive arrangements. But those are not the only offerings in the Fund’s stables.

Below is a quick overview of the most popular IMF products.

Ghana’s practice over the years has been to wait until it is almost desperate before approaching the IMF. It therefore finds quite often that it only qualifies for programs like the Enhanced Credit Facility (ECF) and Extended Fund Facility (EFF) that deserve some of their reputation for reducing political flexibility. IMF programs requiring “structural reforms” of the economy do certainly signal to the market that a country is in a bit of a patch, a factor that can, in certain circumstances, affect borrowing on the commercial market. But there is a lot of nuance.

Kenya, for instance, is actually consuming three IMF products concurrently, all of the “bailout” variety – the EFF, ECF and the RCF. Through these facilities, it has secured nearly $2.2 billion in the last two years alone (twice what the e-Levy is expected to yield in the Finance Ministry’s most optimistic forecasts).

Ghana decided in 2020, like Nigeria, to take advantage of a global COVID-19 response mechanism and go for just an RCF, which is a fairly sweet-deal kind of bailout package with virtually no conditions. It received 738 million SDR, a type of IMF “currency” or unit of account (or roughly $1 billion), whilst Nigeria, because of its bigger economy, bagged 2.45 billion SDR. In both cases, the “program” expired soon after the money hit the account. Behaving just like a normal commercial loan, where the bank generally leaves the borrower to run their business as they see fit.

The above suggests that Ghana has no problem taking IMF money per se. But, like Nigeria, its twin on quite a number of fiscal measures nowadays, it does not appreciate any schoolmaster type tutelage. Which is fine, but a number of strategic issues arise, almost none of which has been properly debated.

Why is the Finance Ministry not going for a Rapid Finance Instrument (RFI) product like Namibia (2020), Senegal (2020), Bahamas (2020), and Costa Rica (2020)? Surely, these are not basket-case countries? The RFI product is also light-touch, with virtually no conditionality. South Africa successfully negotiated a $4.3 billion RFI facility in July 2020. Once the money hit the account, that was it, just like a normal commercial loan. The IMF actually do call these “outright loans”, and packages them with no conditions other than the standard interest and repayment terms.

There is a very important reason why this is a crucial point. IMF money is cheap. Many of its products are interest rate free until the borrowing country exceeds 187.5% of its quota, at which point the rate hits 2%.

Some products like the RCF are not only interest free regardless of amount, they also come with a grace period, typically 5 years during which the country pays nothing.

Compare that with a tranche in Ghana’s most recent Eurobond issuance in 2021. A 7-year $1 billion bond that attracted interest of 7.75%. In very crude terms, Ghana “loses” $57.5 million a year by borrowing a billion dollars in the commercial markets instead of from the IMF. Not chicken feed.

So, if IMF money is cheap, why can there be any concern at all? Well, as you may recall from above, there is also the issue of “national ego” and the more pragmatic concern about “market signaling”. Let’s talk about the latter.

Some observers erroneously believe that an IMF program somehow blocks a country from borrowing on the international markets until the program is complete. This is of course completely inaccurate. Kenya successfully issued a $1 billion Eurobond in June 2021 at a fairly decent rate of 6.3% just two months after securing a $2.34 billion IMF facility. In some ways, getting an IMF facility can actually improve the market’s perception of a country’s creditworthiness. Ghana tested this in 2015 when after enrolling in an IMF program in April it approached the market in October of the same year with a Eurobond issuance. Being at the height of the dumsor crisis, it didn’t get a good rate, but at least it sold.

The signaling issue is thus not open and shut. And, of course, if Ghana believes that national pride prevents it from appearing as if it needs an IMF stamp to be able to access the international capital markets, why does it not try for the big leagues?

There are a number of IMF programs that only the “big boys” go for. They include the Flexible Credit Line (FCL) and the Precautionary and Liquidity Line (PLL). In November 2021, Mexico went for a $50 billion FCL. Chile had earlier collected nearly $24 billion in May 2020. Panama went for a $2.7 billion PLL in the same timeframe. If Ghana genuinely believes that its fundamentals are solid, as the Finance Ministry has said, and that it cannot be seen, in the remotest, to be experiencing a balance of payments situation, then why not test the country’s mettle by going for a PLL or FCL, both of which are only granted, like a revolving overdraft, to countries with sound economic fundamentals so long as they continue to meet the eligibility criteria? Unless, of course, things are not that rosy, and the Ministry is afraid that Ghana may not be eligible for anything other than plain-vanilla balance of payments support.

The last issue to consider is the “competition” between e-levy and an IMF program. Some commentators are promoting a “return” to the IMF as an alternative to going ahead with the e-Levy. This only makes sense if, as some suspect, the government’s intention of passing the e-levy is to convince the market to become more receptive to another Eurobond issuance. If that is indeed the case, then given the political costs of the e-Levy strategy, an IMF program would make more sense, especially when you reflect on the earlier point about how countries have often sequenced their Eurobond campaigns right after entering an IMF program.

If, on the other hand, the government is genuine in its rhetoric about cutting down borrowing, from whichever source, however cheap or well-priced, and getting Ghanaians to fund the greater part of their own government, regardless of the political and economic repercussions, then of course the e-Levy is a superior idea. After all, cheap as they may be, IMF facilities (except the relatively smaller “Catastrophe containment” grants) still need to be paid back.

Somehow, many in the policy community are not too convinced that the government’s recent actions are not merely a show for investors to reopen the doors to the sweet nirvana of Eurobond issuances. Early indications of the government’s domestic borrowing plans do not really corroborate the notion of significantly cutting its overall borrowing appetite.

Whatever be the fact, there is one certainty: neither an IMF program nor the e-Levy can truly address the fundamental issues that have led Ghana into the current ditch: weak productivity in the private sector exacerbated by a high cost of doing business, which in turn is compounded by wasteful spending habits in a fast-bloating state sector.

As I have argued elsewhere, the Ghanaian government has over the last decade become overbearingly expensive to run, with too many price-inflated projects competing for the attention of the politically connected. This has led to a neglect of quality policymaking that can actually boost efficient private sector output. Without the latter, GDP growth will not translate into jobs, innovation, and taxes.

In a way, talk about both e-Levy and IMF-return are distractions from the most critical issues at stake. Even if, depending on the real intentions of the government, one of the two is bound to be superior to the other.

Ghana: A Nation of Tax Thieves?

The recent debate over the proposed e-levy tax has put the spotlight very intensely on the subject of taxpaying attitudes in Ghana.

Ghanaian politicians regularly chastise their fellow citizens for being entitled windbags who complain constantly about every minute failing of the government in providing services and amenities. Lamentably, in the view of the politicians, these same Ghanaians slink down their holes when asked to pay their fair share of tax for the government to obtain the resources needed to meet all their noisy demands.

One former Minister is categorical: Ghanaians just don’t like paying taxes. An activist of the ruling party implicates “dirty politicking” in this attitude of rampant tax dislike and evasion. According to the country’s serving Finance Minister, only 8.2% of working Ghanaians pay tax.

As far as some politicians would have it, a vast proportion of the population is literally made up of “tax thieves” blatantly stealing from the state that which morally and legally belongs to it.

Yet many Ghanaians disagree with the politicians about this alleged aversion to tax.

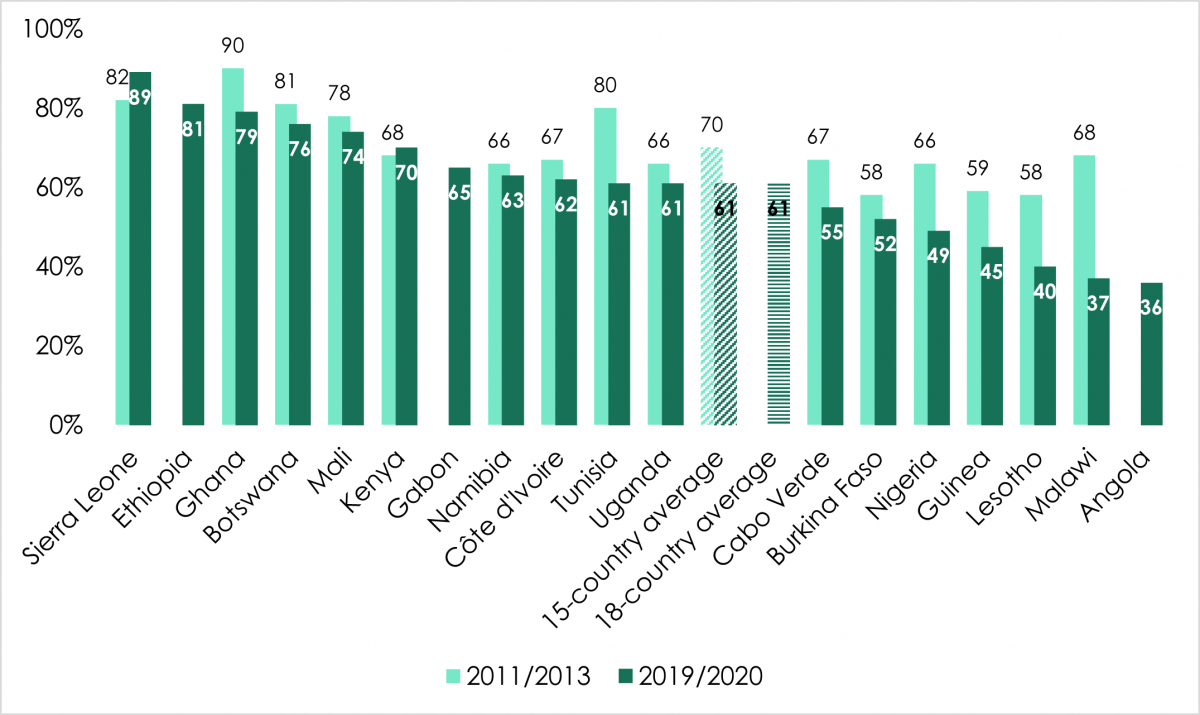

72% of the country’s residents tell AfroBarometer (2019) that they will gladly pay more tax to support the government to deliver on its mandate.

Ghanaians express a far greater willingness to back Government’s tax-levying power than citizens of most other African countries according to AfroBarometer surveys. Even if 10 years of watching politicians pour money down the drain has dampened that enthusiasm a bit (from 90% down to 79%).

Of course, there is no country on Earth where more vigilance and diligence in tax collection would not yield more government revenue.

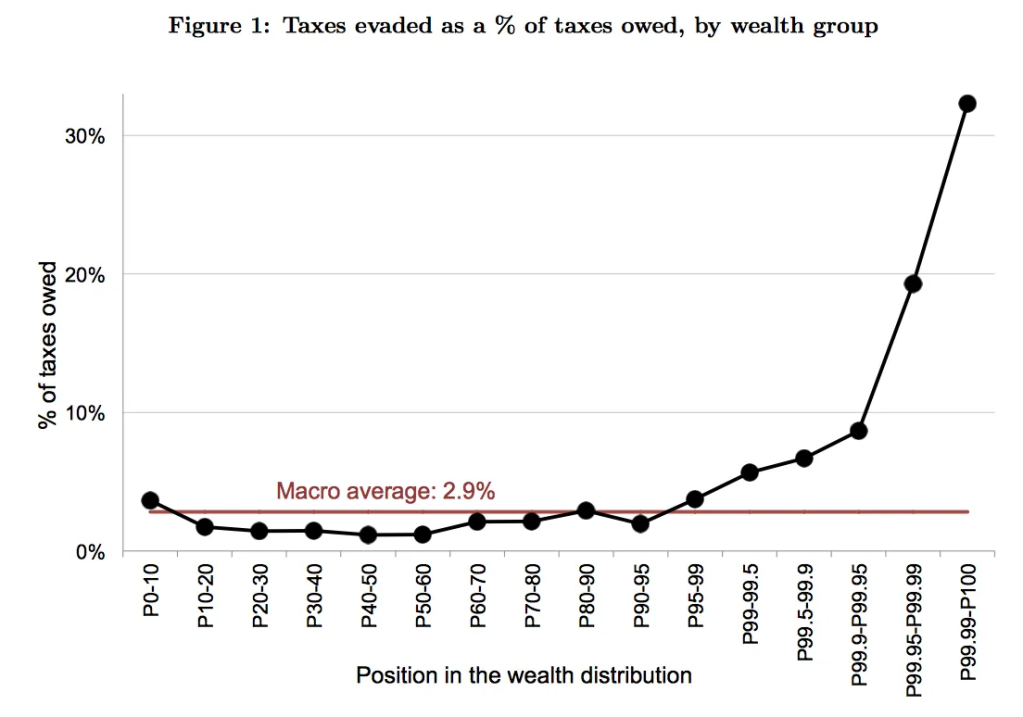

Even in fabulously high-solidarity and egalitarian Scandinavia, Matthew Yglesias estimates that the top 1% of income earners (i.e. rich people) evade 30% of true tax due.

Every government therefore can be expected to try to do more to prevent tax evasion and to minimise unethical tax avoidance. Where we have a problem is when attempts are made to suggest that the situation in Ghana with regard to taxation is particularly dire because Ghanaians are exceptionally unscrupulous and anti-tax. I disagree simply for the reason that the data simply doesn’t support the claims.

Seriously the Finance Minister ought to fire some of his research assistants. Throughout this e-levy debate, they have failed to furnish him with sound data and advice. The claim, made in the international press no less, that only 8.2% of working Ghanaians pay tax is extremely distressing. There is no grounding in fact for this belief.

According to the Ghana Revenue Authority, which reports to the Finance Ministry, 6.6 million Ghanaians file taxes. Based on the provisional results of the latest census in Ghana (2020, postponed to 2021), the true labour force (economically active citizens) of Ghana is just a little under ten million. Thus, depending on whom you believe, the number of tax paying individuals is either a high of 57% of the population (not adjusting for the “economically active but currently unemployed” to allow for easier subsequent comparisons across countries), according to the Tax Authorities. Even if we were to use the Finance Ministry’s own curious compliance data, the resulting figure would be 20.5%. Not 8.2%.

The Finance Ministry does have a point, however, when it complains that the amount of money made in the economy that goes to the government (approximated by the metric known as “tax revenue/GDP”) is smaller than in more developed countries around the world. I have addressed that issue more fully here.

There are many caveats to bear in mind when comparing how much other governments are able to squeeze out of their economy, compared to Ghana’s, however.

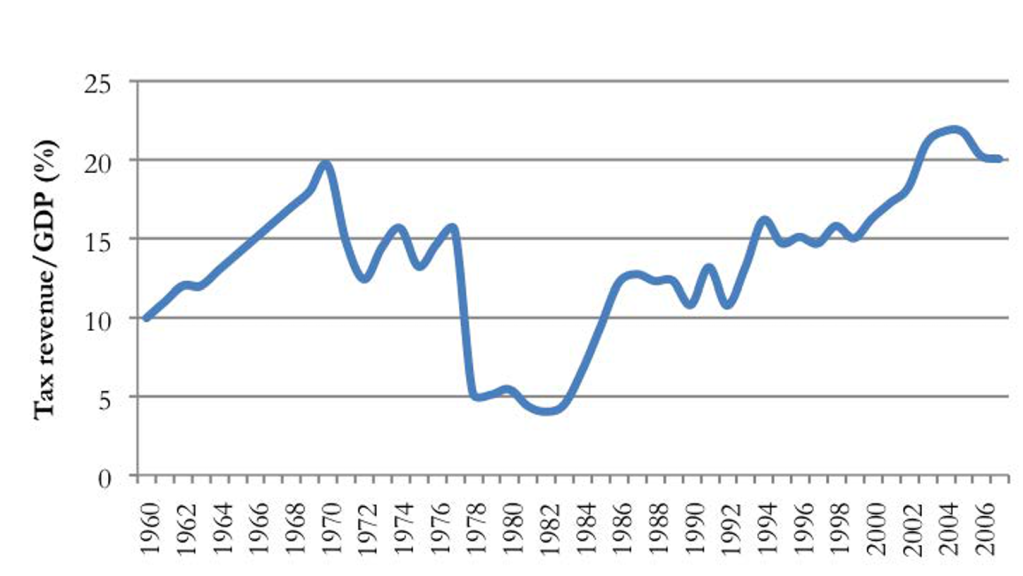

First, the historical evidence does not suggest that the government is able to squeeze more out of the economy when Ghanaians suddenly become upright and scrupulous in between epochs in history. It suggests, rather, that how much government takes in taxes reflects shifts in the relation between the state and business.

In the 1960s when the state run large parts of the economy, and the private sector was young, it was natural for the citizens to pay less tax. As Ghana liberalised, and private sector activity grew, more tax was paid. Then the Acheampong government came in and nationalised large swathes of the economy (for example, the government took 55% in major mines and factories hitherto majority owned by the private sector). State-control took the tax-to-GDP ratio to its lowest in 1981 – 1982, in the heat of the last attempt at a socialist revolution. Tax to GDP continued to climb as the emphasis shifted to private sector empowerment, until the discovery of Eurobonds in 2007, the onset of oil production in 2010, and the start of the gold and cocoa bull super-cycle (in both price and production terms) that is still underway.

Second, as I have hinted elsewhere, the considerable boom in oil, gold and cocoa prices and production over the last decade, backed by copious quantities of eurobonds, have considerably shifted the momentum in the economy towards the government-controlled center, to the detriment somewhat of the private sector. Without considerable private sector productivity growth, it is hard for taxes, versus other forms of revenue like royalties, to grow in line with or faster than GDP.

Third, the structural issues in the economy are also reflected by the sheer number of persons in various sectors where income is highly irregular or is taxed in ways making personal and corporate/enterprise taxation completely incongruous. For instance, 75% of Ghanaians farm, fish, “buy and sell” or engage in low-level artisanship. Farmers sell food with high implied non-state subsidies created by a massive differential between farmgate and urban retail prices. Cash crop farmers must actually sell at the government-dictated price so that the state can take a margin. These are all implicit taxes.

Furthermore, due to high domestic borrowing, central government financing (money printing, among others), and other “money emission” factors, coupled with a tendency to inflate away the value of the money it has borrowed from citizens, the government of Ghana enjoys high rates of seigniorage and inflation tax. As noted by many commentators in this sub-discipline, inflation tax has a habit of flipping at an inflection point and yielding negative returns. The chickens may have simply come home to roost in Ghana.

Not surprising then that two West African countries whose governments consistently lament their low tax to GDP ratios, Ghana and Nigeria, have also historically benefited the most from inflation tax.

In short, letting the data do the talking reveals the startling truth, in deep contrast with the standard commentary in Ghanaian policy circles, that Ghana actually outperforms many peers and superiors when it comes to registering people to tax them.

A person holding brief for the Finance Ministry is likely at this juncture to push back. Mobilising people into the tax net does not by itself mean that people are still not cheating the treasury. True, but that is not a peculiar Ghanaian issue. At any rate, politicians have consistently been twisting the truth by making it look like the “tax net” in Ghana is not “capturing” millions of shady characters with sackfuls of cash under their mattresses. What the above clearly shows is that over the last decade or so we have brought millions into that tax net. At least, they are visible.

We can now tackle the question of whether beyond the structural reasons (inflation, natural resource dependency, debt-fueled-but-low-productivity-growth etc.) I have provided above and elsewhere, there is strong reason to believe that under-declaration is particularly rampant in Ghana.

Let me get this out of the way: there is no reason to doubt that there is considerable under-declaration. As a brilliant friend of mine at a top consultancy likes to remind me, the Ghana Revenue Authority meets more of their stretched targets than they miss. Somehow, in some years, they manage to find the money lurking somewhere in the economy regardless how aggressive the target is set. The question we need to ask though is: how widespread is this practice, really?

If it turns out that we have a few ultra-wealthy cabals doing most of the under-declaration, as opposed to the general masses of the long-suffering people of Ghana, then the key thesis of this essay holds: there is no evidence that Ghanaians generally don’t like taxes (anymore than the average human), aren’t paying taxes or are particularly unscrupulous about taxes. It is entirely up to the political class to rein in their cronies in the cabals, currently enjoying political protection, hoarding the wealth and refusing to chip into the national kitty.

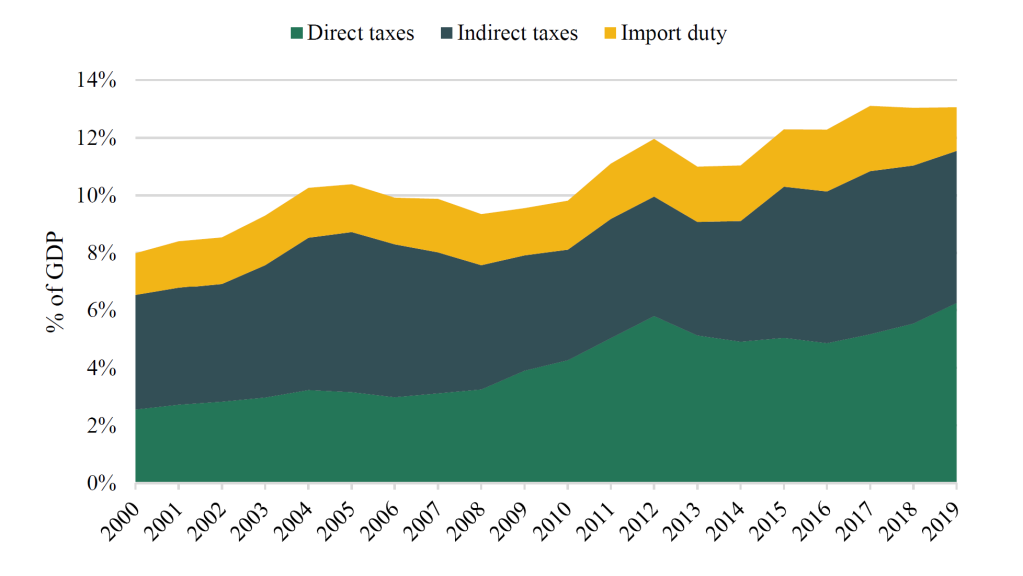

To make progress along that line of inquiry, it is important to unpack the recent decline of revenues-to-GDP from 22% in 2005 (per Matthew Ocran’s calculations) to roughly 14% today (beyond the structural factors I have hinted at above, that is). What really in the tax basket has been leaking out?

A 2021 report by the UK’s Institute of Fiscal Studies (IFS) reveals much. (As a side note, it is curious that the IFS in its home base of Britain is regularly counted on to produce independent revenue forecasts for proposed taxes, like our e-levy here; but in Ghana, the government routinely refuses to encourage such rigorous tax analysis and forecasts before introducing its tax measures.)

Let me quote the IFS:

Tax collections on imported goods have become far less important in the revenue mix, though they remain significant: 30% of overall tax revenues were collected on imported goods in 2019 (including VAT on imported products), compared with 54% in 2000. The contribution of import duties specifically to total tax revenue declined from 18% in 2000 to a low of 12% in 2019.

And:

Much of the growth in Ghana’s GRA-collected tax revenues since 2000 has come from increased corporate and personal income tax and VAT and similar taxes, though revenue growth from the latter two has stagnated more recently. These taxes made up over 70% of total collections in 2019 – up from 57% in 2000.

In short, whilst Ghanaians have been paying lots more in income taxes on both their personal and business income, the ports have been leaking.

There are two main ways to account for those leakages. First, graft. The Vice President has described the corruption at the Port as “unbearable”. Second, tariff policy. The average tariff in Ghana is about 92.5% of the value of the item being imported. Essentially, on average, importers pay almost the equivalent of the price of the good being imported to the government as tax.

The high tariffs are a clear incentive to bribe one’s way through if one has the means, so the two main causes are interconnected. But given the implied import-substitution and infant-industry protection bent in current Ghanaian trade policy, a significant reduction in tariffs is unpalatable to almost everyone in the policy establishment today.

Below is a graph showing how Ghana compares with other countries its policymakers and other commentators like to compare the country to. Note the presence of both liberal and “developmental-statist” economies on the list. It is clear that imports have become so expensive over time that the growth in their volumes has been dropping, leading to a drop in revenue from import duties and other port-levied taxes. The trend is furthermore being exacerbated by bribery and corruption.

The truth is: when you look at the part of the revenue mix obtained purely through GRA collections (as opposed to the broader measures of “revenue” used elsewhere in this essay), what we have is a stagnation due to a declining trend in import tax collection, not fully offset by a growth in personal and corporate income tax collection!

The alarmism by politicians, targeted at the conduct of citizens, is completely unwarranted and the media must stop enabling it and start asking hard questions.

Of course, politicians will still push back. They will say things like: people are doing many side jobs and not declaring income so the rise in income tax revenue is purely as a result of the burden falling on a smaller and smaller subset of taxpayers.

Whilst there is no doubt about there being a skewed burden that must be corrected over time, this has become something of a universal burden brought about by a growing concentration of wealth.

In the US, for instance, the top 20% pay nearly 70% of the taxes.

In Singapore, the top 20% of tax payers account for 91% of total tax revenue. Only 7.8% of Malaysia’s 1.25 million registered enterprises pay any tax at all.

So, if a Finance Ministry Mandarin is tempted to argue that Ghana is yet to see any significant benefit from boosting registration of taxpayers, they should temper their sorrow by checking with India where aggressive taxpayer mobilisation saw filings grow to 57.8 million. Yet, those actually owing the Indian government dropped to 14.6 million (coupled with massive numbers of Indians now entitled to tax rebates/credits). To repeat: over a period of 8 years, the number of persons registered for tax but who don’t have enough income to pay any tax to the government increased by 300% in India.

It is not a one-way street. The more government pries into people’s incomes, the more likely some of them are going to realise that they don’t actually get enough help from the government and therefore it is the government that in fact owes them money.

In 2019, 37% of even American taxpayers assessed as owing tax didn’t have the money to pay. In recent years, Indonesia has seen spells where less than 1 million citizens are able to pay tax out of a population of over 270 million.

The last rebuttal to any Finance Ministry Mandarin pressing the old charge of ruling a nation of tax delinquents is wastage.

I am not even talking about the incongruity of tax aggressiveness in a context of high tax burden in a country where many are struggling to make ends meet and therefore only a shrinking number of people shall increasingly be responsible for most of the tax paid, as is the case elsewhere, and how therefore any wastage of taxes may impact tax morale. I am talking specifically about why the government feels that Ghanaians pay far less tax than they can afford when the data says otherwise. And when Ghanaians are indeed subject to some of the highest tariffs and consumption taxes in the world. Just check out comparative VAT rates below.

Or compare aviation taxes in Ghana with what pertains in its rival “aviation hub” aspirants in the region. Ghana charges double the rate in Rwanda and Kenya, and nearly four times the Ethiopian amount. Yet, it insists that it is on course to eclipse them as a continental aviation nexus. Talk of hubris.

No I don’t mean any of that at all. What I mean by “waste” here is the sheer cost of doing government in Ghana. Ghanaian state-subsidised football administrators regularly requests, and often receives very close, to three times the amount their Nigerian and Kenyan counterparts get, and ten times what their Malawian and Gambian compatriots receive.

When Ghana builds bridges or airports, a careful examination of the costs (including borrowing costs) would inevitably show that, pound for pound, they tend to be twice or thrice more expensive. This is the case when you compare Kotoka Terminal 3 in Accra with the bigger 3rd terminal at Bole International in Ethiopia; or the planned Volta River Bridge in Ghana with the Makupa bridge in Kenya.

In short, the government of Ghana has been harbouring this mistaken notion of Ghanaians being inveterate, incorrigible, tax thieves because it feels that it is being squeezed. However the “squeezing” is entirely the doing of the state, and the victim is actually the people.