In the 24 hours since my comment on the e-Passport controversy, more information, especially a video of the key ceremony in Montreal, has emerged to show that the situation is even crazier than initially thought.

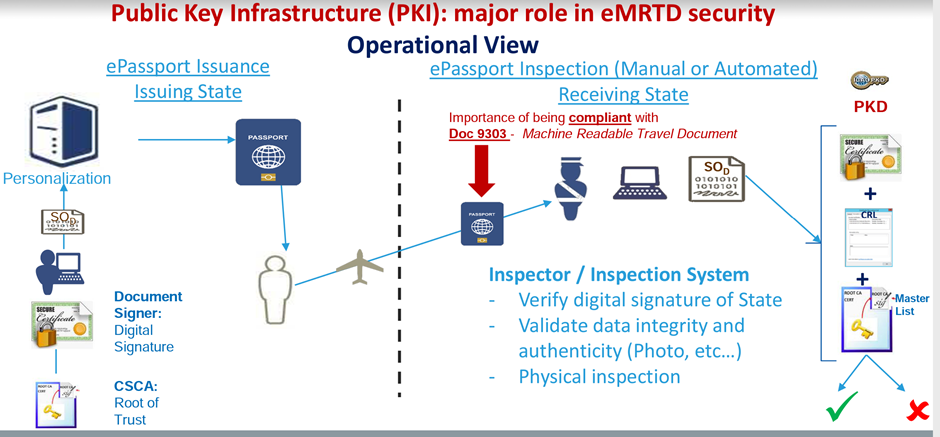

It is clear from the video that the ICAO officials who received the Ghanaian delegation were under a completely different impression about the Public Key certificate (think of it as a very hard to forge “electronic signature” for the state of Ghana) that the Ghanaians wanted to submit to the ICAO Public Key Directorate (PKD).

They clearly thought that it was meant for the other 81 governments in the PKD to be able to authenticate an electronic chip embedded in the Ghanaian Passport, not a national ID card.

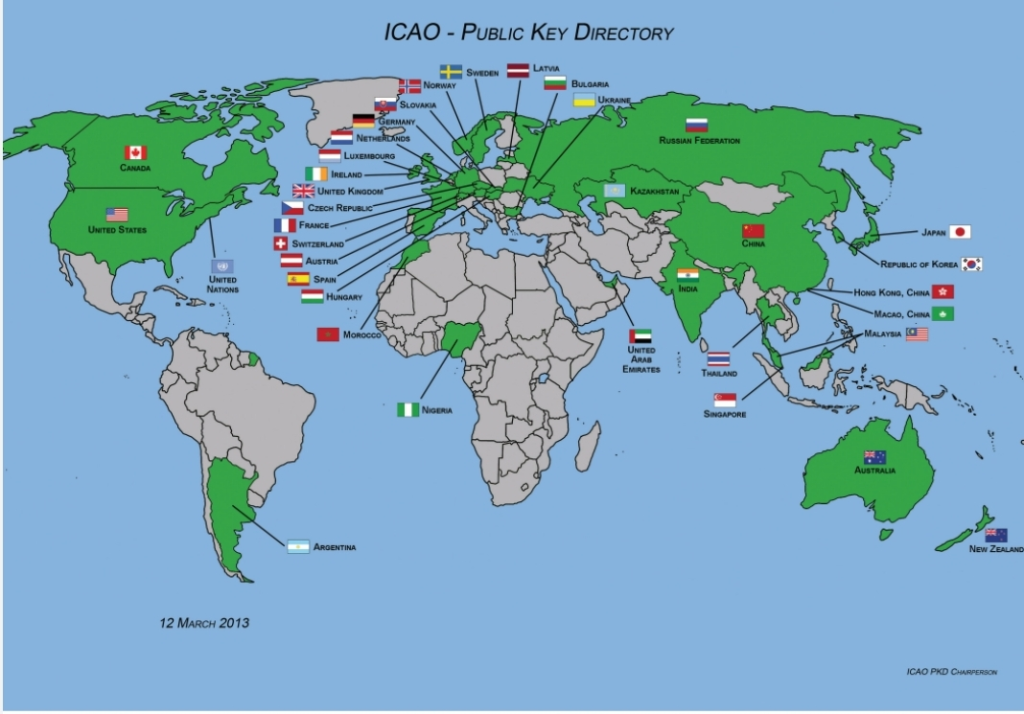

The remarks of both officials who welcomed the delegation expressly relate to how Ghana’s passport would now be more secure from fraud than has been the case in the past. The occasion was meant to be celebratory. A decade ago, only two African countries were part of the PKD – Nigeria and Morocco. Ghana’s joining takes the number to an impressive 15.

As it turns out, the Ghanaians had no intention to use the certificate for the Ghanaian passport, which is still one of the few in the world without an electronic chip (one of only 9 in Africa), making it highly subject to abuse. In a famous forensic study, 46% of Ghanaian passports tested turned out to be fake.

What is even more bizarre about the whole saga is that last October the German company that built the Ghanaian solution being used for the PKD enrolment, Cryptovision, announced how proud it was that its technology was being used to turn the Ghana Card into an e-Passport. They were educated about their misconception and then compelled to correct the statement to read that the Ghana Card is now an electronic Personal Identity Card, not a ePassport.

Considering that Cryptovision is the company that built the chip solution and software, the CAmelot platform, being used by Ghana to broadcast its national electronic signature through the ICAO PKD, it should at least know what the real arrangement with ICAO was.

Indeed, the project scope negotiated by Cryptovision’s Adam Ross for the Ghana Card in 2013 explicitly describes an electronic personal identity card rather than a e-Passport.

e-Passports, as I have tried to explain in detail in two previous articles, constitute a special category among electronic identity cards generally because they are meant to be embedded in passports. Passports have a unique capacity as travel documents already accepted across the world for human mobility purposes due to the dictates of clear international law.

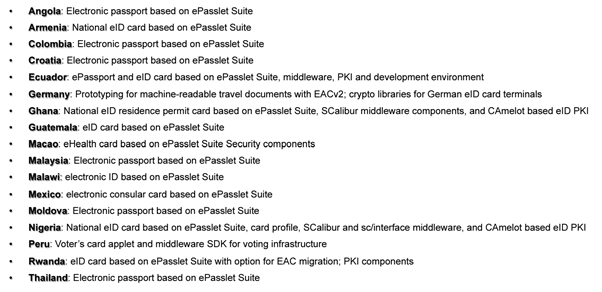

As Adam Ross himself has outlined below, Ghana did not engage Cryptovision to customize its ePasslet solution for a e-Passport solution as countries like Angola and Malaysia did.

It is thus completely mind-boggling that Ghana, knowing all this, would still send a bevy of senior officials, including its resident Ambassador to Canada, to Montreal to attend a key ceremony, ignore the official publicity template issued by ICAO in the key ceremony dossier, and then announce to the world that ICAO has accepted the Ghana Card as an e-Passport, when its base solution is NOT configured for that purpose.

Here is how ICAO defines the eMRTD functionality:

a Machine Readable Travel Document (MRTD) that contains a contactless Integrated Circuit (IC) chip within which is stored certain specified MRTD data, a biometric measure of the passport holder, and a security object to protect the data with Public Key Infrastructure cryptographic technology, and that conforms to the specifications set forth in ICAO Doc 9303.

It further defines a “participant” (i.e. member state like Ghana) in the PKD scheme as:

a Contracting State or any other entity issuing or intending to issue eMRTDs who follow these Regulations for participation in the ICAO PKD.

Professor of Law, Adam Muchmore, describes the distinction between passports and other identity documents, as follows:

Passports, as prima facie evidence of nationality,’ are “normally accepted for the usual immigration and police purposes.”‘ In other words, states take daily legal action on the basis of passports issued by other states, without taking time to investigate whether the passport holder is “really” a national of the issuing state…A passport in this case is different from a national identity card, addressed only to other actors within the issuing state. [Emphasis not author’s.]

A passport’s position in international law is so fortified that no identity card however supported by the interplay of commercial and political interests in a country can usurp its role without consequence.

The principal legal specifications on the subject of electronic travel documents (or, more precisely, “machine readable travel documents (MRTDs)”) binding ICAO itself is the so-called “Doc 9303”. The 8th edition of which was released in 2021. The broader legal framework for the whole business of travel document technical specification can be found in Annex 9 to the Chicago Convention, the world’s main body of international aviation law.

In 2005, the standard to which MRTDs should conform was agreed by the ICAO member states and 2015 was set as the deadline for the phasing out of non-conforming travel documents. Doc 9303 has since been kept up to date with all essential technological evolution.

The specification defines an ePassport as:

Commonly used name for an eMRP. See Electronic Machine Readable Passport (eMRP).

An eMRP, on the other hand, is defined as:

A TD3 size MRTD conforming to the specifications of Doc 9303-4 that additionally incorporates a contactless integrated circuit including the capability of biometric identification of the holder. Commonly referred to as “ePassport”.

What the term “TD3” means can be found in Part 4 of Doc 9303.

Parts 5 and 6 of the same technical document describe other machine-readable official travel documents specified in various bodies of international law, especially those dealing with crew, refugees and human rights.

Section 2 of Part 4, relating to the description of ePassports, describes the form factor (i.e. how an ePassport should be presented) as follows:

The MRP shall take the form of a book consisting of a cover and a minimum of eight pages and shall include a data page onto which the issuing State or organization enters the personal data relating to the holder of the document and data concerning the issuance and validity of the MRP. After issuance, no additional pages shall be added to the MRP.

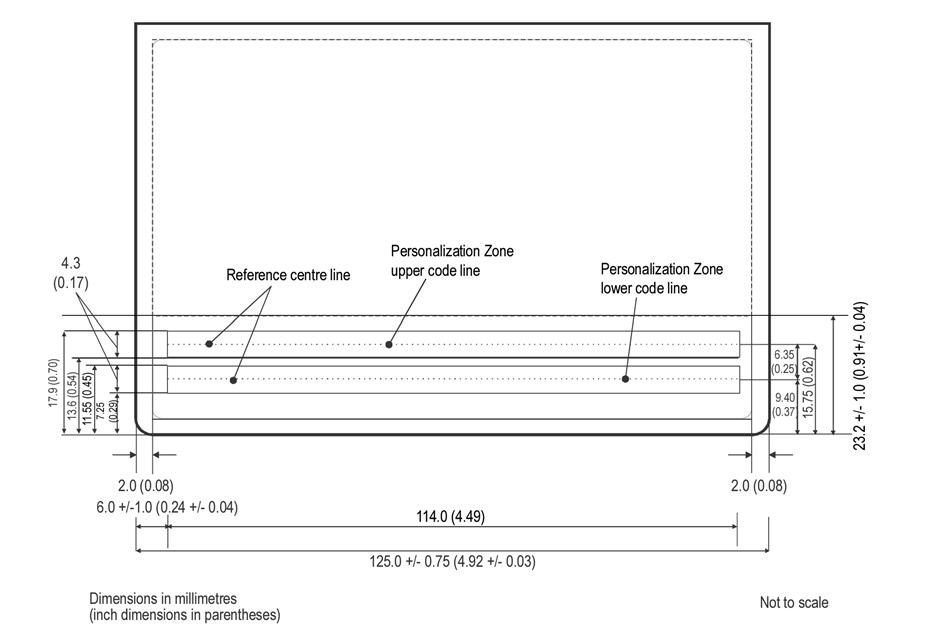

Section 2.2 goes further to specify the dimensions of the booklet:

The nominal dimensions shall be as specified in ISO/IEC 7810: 2019 (except thickness) for the TD3 size MRTD, i.e.: 125.00 mm (4.921 in) wide by 88.00 mm (3.465 in) high

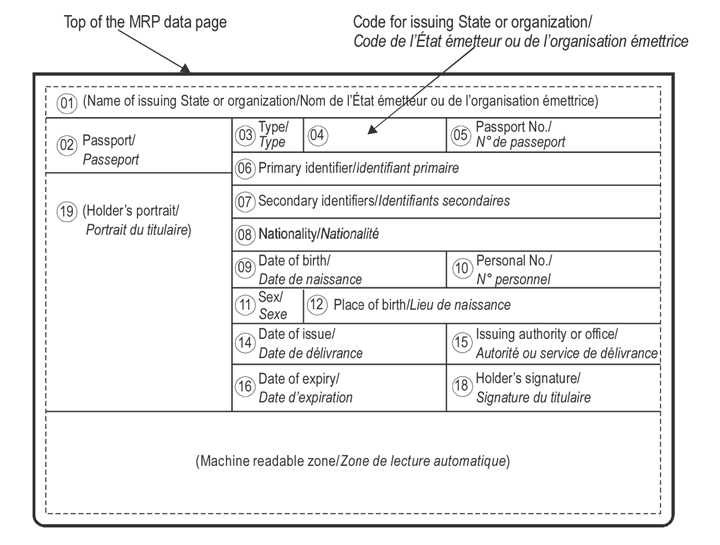

Part 4 also presents the all-important machine readable zone in the drawing below:

And furthermore specifies the biodata page as in the diagram below.

Even clearly itemising which zones are mandatory.

It then presents several examples of conforming pages of a compliant e-Passport, such as this one:

Such is the serious technicality of what is at stake here. It is evident from all the preceding that ICAO indeed had no authority to go contrary to its own enabling regulations and authorize the Ghana Card, which simply does not conform to the specification (contrary to several assertions by government of Ghana spokespersons) to be used as a ePassport.

Even more emphatically, the government’s continued insistence that the Ghana Card is a ePassport is both incorrect and embarrassing. It puts ICAO in a tight spot since the government refuses to accept the former’s informal clarification. The official posture of the government is to doggedly hold on to its position despite clear evidence of confusion in the aviation community. In this strange conduct, the government is aided by pliant public actors who can’t or won’t call it out.

Yet the PKD as structured requires clarity as to which documents precisely a member is applying its certificate to.

The live verification protocol of the PKD is a tight security system based on rules and standard operating procedures.

The overarching principles for the establishment of the PKD are set out in the procedures as follows:

1. The ICAO PKD has been established to promote a globally interoperable ePassport validation scheme for electronic travel documents to support ICAO’s strategic objectives to improve aviation security and improve the efficiency of civil aviation.

2. The benefits of ePassport validation are collective, cumulative and universal.

3. The objective of the ICAO PKD is to support validation of all ePassports that are widely accepted for travel and identity verification purposes by ICAO Contracting States.

Extract from ICAO PKD Procedures Manual

No country in the world that has joined the Scheme has ever thrown into question the conformance of the procedures and state practice, on the one hand, with the ICAO PKD enabling legal documents, on the other hand, in the way we have witnessed these last few days.

The time for wordplay and needless argumentation to end is now. The government of Ghana should formally retract its ePassport claims for the Ghana Card and immediately take steps to transition the indomitable Ghana Passport to a full electronic passport (with an ICAO-compliant chip) so that the country can fully benefit from the fees it is paying to be part of the ICAO PKD. A serious Minister of Foreign Affairs would make a clear statement on this matter, in their capacity as the seniormost official responsible for the sanctity of the Ghana Passport.

And to the extent that international law makes the question of nationality of a passport holder moot, it is also time for the government of Ghana to rescind all the rules made by the National Communications Authority, the Bank of Ghana, and other overzealous agencies barring holders of the Ghanaian passport from accessing telecommunications and banking services in Ghana. No country in the world has done this. Ever! Ghana is not that special.

We know that the investors behind the country’s heavily outsourced Ghana Card intends to meet their target of $1.2 billion of revenue in a few years. But it should not be at the expense of the country’s international image and the rights of its citizens.