The first time I read Amartya Sen’s The Argumentative Indian, I laughed and said to myself, “the eminent economist has probably never met a Ghanaian in his life!”

My reaction was tongue in cheek, however, since Professor Sen’s main thesis is not that Indians just love arguing for arguing sake, but rather that the subcontinent’s heritage of intellectual pluralism is foundational to its unique democratic project.

Ghana’s “argumentative tradition” is more literal; in Ghana, everything is debatable!

On 6th November 2021, I appeared on Citi TV’s Big Issues program, where the topic of discussion was Ghana’s “digitalization agenda”, championed by the country’s Vice President, a subject I subsequently wrote about here. In the studio was the Executive Secretary of the Vice President, who also doubles as a Chief in both the Sefwi and Mamprusi areas of Ghana.

A lively debate ensued about a flurry of PR statements from the Vice Presidency touting the national ID card (the “Ghana Card”) as a “e-Passport” due to Ghana’s decision to join the ICAO PKD Network. During the discussion, it became apparent that unnecessary confusion was being created about how the development was a benefit conferred on Ghana because of the Ghana Card, seeing as that misconception is completely untrue. The Ghana Card has no role to play. It is not the card that has been “recognised” but Ghana’s “public key”, which the lay reader can think of as a “highly secure electronic signature”. That key can be embedded in any ID document at all. After the show, I wrote my article and considered the matter closed.

Until I woke up a few days ago to an official Ghana News Agency report splashed across Ghana’s media networks that ICAO has “recognized the Ghana Card as an e-Passport”. The subsequent rebuttal of this bizarre and incoherent claim by ICAO itself did nothing to quieten the controversy. Debate continues on social media even now, with government affiliates still pushing the narrative of the “Ghana Card having become an e-Passport” and opposition activists having a field day with the ICAO statement.

But what makes this a uniquely Ghanaian contrived controversy?

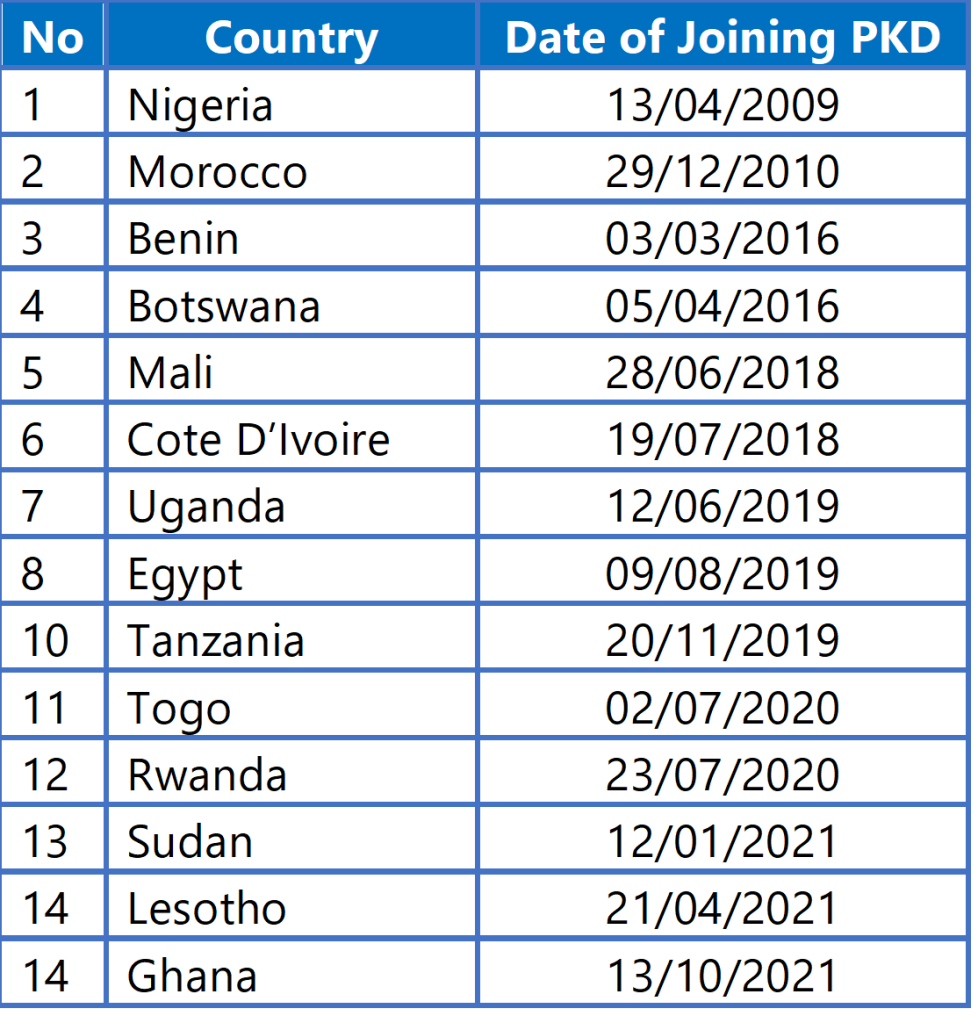

Because, first of all, no country in Africa that has joined the ICAO PKD network has succeeded in transforming it into a high-stakes, high-octane, political jamboree. See the list below.

Nigeria has been a member of the PKD network for more than a decade, but I don’t recall seeing a single episode of government-opposition tussle over what this means. In each of the African countries that have chosen to publish their public keys in the ICAO directory and comply with the smart chip standards that makes verification of the public key possible by the other 81 countries that are part of the process, the whole endeavour has been treated as an obscure technical development.

Joining the ICAO PKD simply means that other countries in the network can confirm that the “electronic signature” on documents issued by a joining government are genuine. This process itself has got nothing to do with e-Passport functionalities per se, which are about encoding the principal information of the traveller (including biometrics) in electronic format and the acceptance of the document in which the electronic information is embedded. India has been a participant of the PKD since 2009 but it is only now about to add e-Passport functionality to all its passports (some Indian officials have had e-Passports since 2008).

Uganda has been part of the PKD for nearly three years now but is only now about to transition from machine-readable biometric passports to a full e-passport. Indeed, Ghana initiated that process in 2014 but could not complete the contracting to complete. Of course, Ghana had not join the ICAO PKD when it was contemplating this transition in 2014 but one does not need to be part of the ICAO PKD to issue e-Passports.

In fact, there are countries like South Africa and Kenya with advanced digital travel identity systems in Africa that are not yet participants in the PKD system. Some countries like Taiwan that have migrated from machine-readable to the e-Passport model cannot directly participate in the ICAO process because of geopolitics, even though Hong Kong and Macao, autonomous regions of China are both participants.

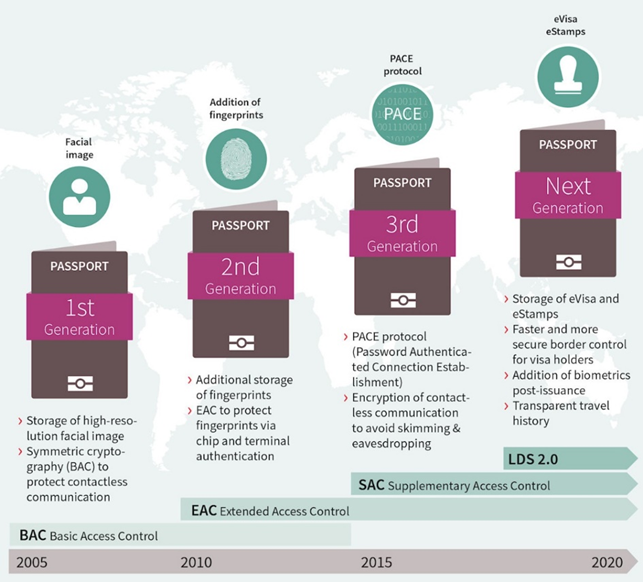

So, this is a very simple matter. In the past, passports could only be read visually. The border agent/immigration officer would process the traveler’s entry by typing their details into host/receiging country’s system. The world eventually moved on to the use of machine-readable passports whereby the immigration officer just scanned the passport and the computer automatically extracted the information.

In 1998, Malaysia pioneered the use of biometric passports, the next step in the evolution. The biometric signature of the passport holder was transformed into a format that could be read by scanners at many immigration counters around the world. For this to be possible, an 8 kilobyte integrated circuit card (or “chip”) was embedded in the passport to hold the traveler’s biometric data.

The problem was that, for full security, it was important for this biometric data to be encrypted else a criminal could cut their own chip and embed false data. But encrypting the data also meant that some method had to be found for the destination country’s immigration officers to decrypt and read the data on the card. This is where the ICAO PKD came in handy.

In 2004, ICAO published a specification of how all countries should store and secure information in the passport on the chip, and Belgium became the first to comply, and one of the most enthusiastic upgraders in the world. In 2007, ICAO also established a secure channel, the PKD, through which countries can decrypt the secure information in the e-Passport chip.

Note that all this while we have been talking about the passport that everyone is familiar with, that same precious booklet that for some is the symbol of true freedom. We have not talked about smartcards. In fact, there is no expectation that a country will use a smartcard for any of this stuff. A “e-passport” is a functionality not a device.

Of the 150 countries that issue passports with some e-passport capability, virtually all of them integrate that capability into the passport booklet itself, primarily because that is the one that all countries accept and is currently universally compatible with the global visa regime. Thus, countries have focused their investments on incorporating e-passport functionality into their passport booklets. In fact, some countries like the United States deny their visa waiver programs to nationals of countries that do not do this.

Notwithstanding the fact that many e-Passport issuing countries are not part of the ICAO PKD, commercial vendors have found a means to embed the capability to read most of these passports in scanners and software that they market to governments around the world.

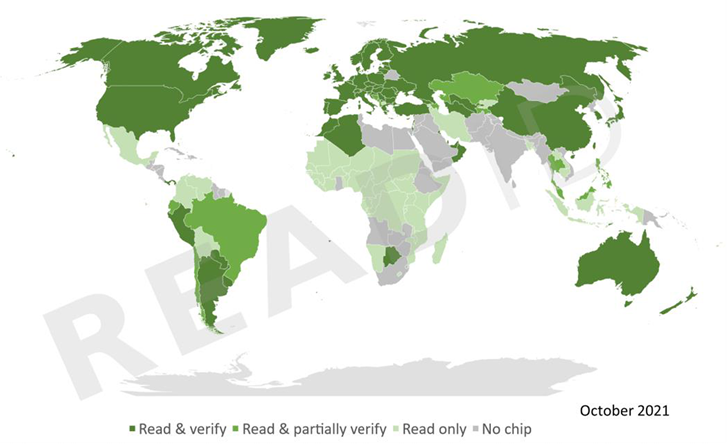

Ghana is, in fact, one of the few countries in the world still issuing passports with no chips. Passports that therefore cannot be securely validated by commercially available software or through the ICAO PKD as the map below shows.

With more and more countries embedding e-passport capabilities into their passports, making them readable in more and more airports, there is a steady race towards a period where visas will also be “written” to chips in passports issued by other governments. But this will in no way lead to an abandoning of passports for smartcards because electronics can and do fail. Hence, visual and optical reading will for a long time remain necessary. Passport booklets are not going anywhere, only the chips in them will evolve.

So where does the Ghana Card comes in? The Ghana Card as I have stated elsewhere is a major distraction from the critical task of securing the Ghana passport! Ghana is a member of the rapidly declining group of countries whose passports still have no chips (as clearly evidenced in the map above.)

Ghana’s laggard status here is really problematic considering the continued abuse of the Ghana passport by identity criminals and the associated risk to national security. And considering the unfavourable attention the country has courted internationally. Yet, because of powerful vendors behind the Ghana Card and the fact that it is a massive, highly commercialized, Public-Private Partnership (PPP), there is a crass attempt to divert resources to it at the expense of the beleaguered passport, something that a serious Ministry of Foreign Affairs wouldn’t and shouldn’t tolerate.

Of course, there are countries that have embedded chips in their national ID cards like Ghana has done. And some of those chips are ICAO PKD-compliant. But as can easily be seen by analysing the ICAO PKD key ceremony, it is not ICAO PKD-compliance that confers the e-Passport functionality. Joining the PKD, at the cost of less than $30,000 a year, simply means that any ID document that Ghana electronically signs can be verified by other members of the PKD. But the overwhelming majority of countries apply the PKD system to their normal passport booklets instead of national identity smartcards (like the Ghana Card).

To activate a e-Passport, the chip should be incorporated in a document that is already accepted as a passport by a wide range of states. Interestingly, even among the 82 PKD states only a little more than half actually connect to the system to validate ID documents operationally. In short, the vast majority of states have border systems set up to verify passport documents by conventional means.

Right now, more than 90% of the countries in the world where Ghanaians may want to travel accept only the Ghana passport for the obvious reason that they are not party to the ECOWAS Biometric Identity Card (ENBIC) accord (which itself is still not fully operational since Senegal pioneered compliance in 2016). So the decision to prioritise the Ghana Card over the Ghana Passport for smart chip functionality is quite frankly bizarre.

Even within the West African region, the smart card authorization systems needed to read the ECOWAS Biometric Identity Card format do not exist in several airports. Most airlines are equipped to read the MRZ in the standard passport (that is why you see the check-in agents swiping the edge of the biodata page when checking you in) and not smartcard chips, nor are they allowed to access the ICAO PKD LDAP as yet (except in pilot form). Airlines around the world have security systems geared to the conventional MRZ in passport booklets.

Whilst the Ghana government has the sovereign right to tell airlines to just look at the smart card and allow people to board, there are security implications. For example, in some countries like the United States, which have laws like the REAL ID Act, airlines must confirm that international travelers are in possession of a passport or specifically authorised documents.

The key issue here is that whilst the passport remains the most critical travel document in the world, the government of Ghana, for totally unclear reasons, has decided to neglect its security, and is instead prioritising a domestic ID card. Its agents and spokespersons are on social media arguing over everything else apart from the essential question of why.

Talk about the Argumentative Ghanaian!